The Second World War began with the German invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939. The Netherlands declared their neutrality, a position they had maintained during the First World War. But on 10 May 1940, the German Wehrmacht attacked, Queen Wilhelmina and the Dutch government fled into exile in London. After the bombing of Rotterdam and the destruction of Middelburg, the Dutch army capitulated on 15 May 1940. The last isolated Dutch combat troops surrendered in Zeeland on 17 May.

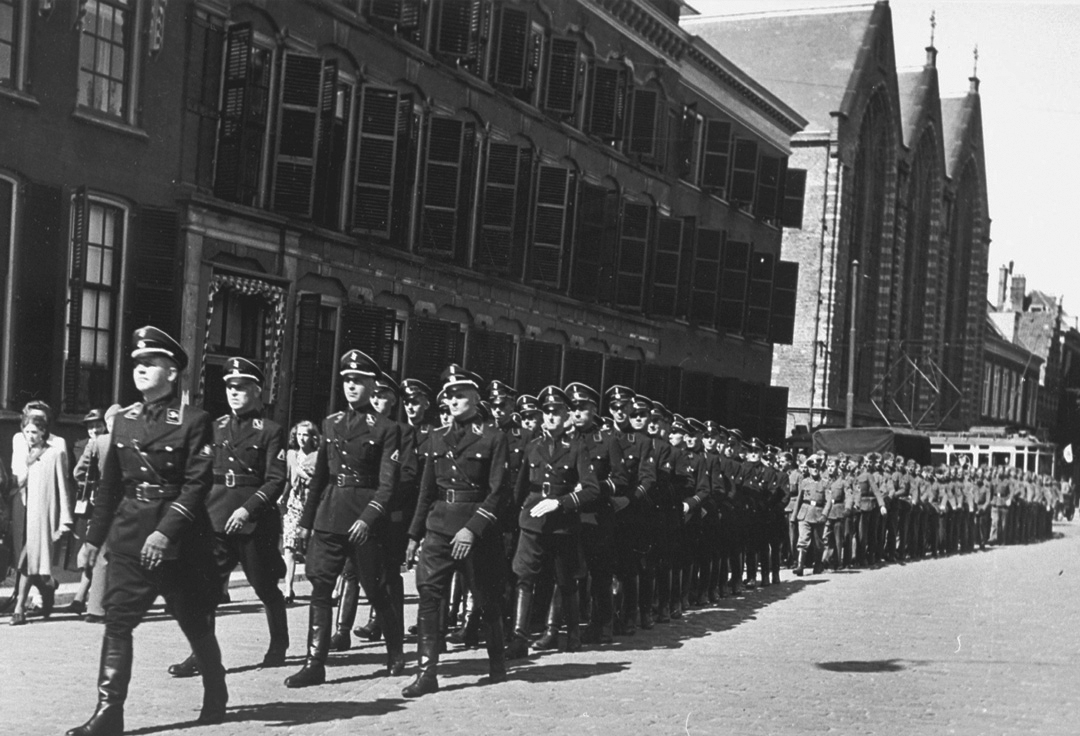

At this point, the Germans took control, and Adolf Hitler appointed an Austrian, Arthur Seyß-Inquart to the position of Reich Commissioner for the occupied Dutch territories. Hanns Albin Rauter became responsible for security and police matters in the Reich Commissioner’s office and served as Heinrich Himmler’s representative in the Netherlands.

In his 37th edition of the second OWC volume, Curt Bloch dedicated a poem to the powerful Nazi Heinrich Himmler. In it, he says, among other things, “Whoever hears the name of Heinrich Himmler will turn deathly pale in terror.”

The German occupiers initially sought a good relationship with the local population because they considered the Netherlands a sister nation. The Dutch economy improved soon after the occupation, as the previous enormously high unemployment rate decreased with the “war effort”. Many Dutch citizens voluntarily went to work in Germany. Dutch companies that produced goods for the German market enjoyed an increase in revenues.

From 1941, the occupiers systematically conducted raids. Fr example, after disturbances in Amsterdam provoked by Dutch National Socialists, German propaganda blamed Jewish citizens. Throughout the year, similar raids took place in the eastern provinces of Overijssel and Gelderland, where hundreds of Jews were arbitrarily arrested, deported to the Mauthausen concentration camp, and killed. These measures caused great fear among the population, and soured Dutch opinion about the German occupiers. Additionally, the first resistance groups formed, although the majority of the Dutch population accepted the new regime.

Resistance against the German occupiers is a recurring theme in Curt Bloch’s “Onderwater-Cabaret.” He even composed a Dutch song with sheet music on the topic: The Resistance Song, in fourth issue of the third volume.

Resistance activities included writing and distributing prohibited publications, collecting military information to support the Allies, hiding persecuted people, and developing escape routes for them and for downed Allied pilots.

In May 1940, the population of the Netherlands was approximately 8.7 million. Depending on the definition of “resistance,” the number of Dutch resistors ranged from 25,000 to 60,000, about the same as the membership of the Dutch Nationaal-Socialistische Beweging (NSB).

From 1931 to 1945, the NSB was initially a fascist and later a national socialist party. The NSB experienced a rapid rise, with only 1,000 members in 1933 growing to over 100,000 six years later. After the German occupation, the NSB was the only allowed party, but its popularity declined with the start of the Second World War and the German occupation. By the end of the war in May 1945, NSB membership declined to only a few tens of thousands. The founder and leader of the party was Anton Adriaan Mussert.

Curt Bloch composed numerous rhymes expressing his contempt for Mussert and the NSB. On 3 June 1944, he published The Dogs of the NSB.

A propaganda campaign organized by Commissioner Schmidt, in which the SS recruited volunteers for the “fight against Bolshevism” from 1941, was quite successful. Around 22,000 Dutch people volunteered for service in the elite unit during the war.

From 1942, the supply situation deteriorated as the German occupiers increasingly exploited the Dutch economy.

After the enormous defeat of the German 6th Army at Stalingrad, more German men were conscripted into military service to compensate for the losses. The vacant positions were filled by people from the occupied territories. In late April 1943, all male Dutch citizens between the ages of 18 and 35 were ordered to register for possible work in Germany, which caused significant unrest and a nationwide strike.

The German compulsory measures affected nearly every Dutch family but could not be implemented as planned. The Germans went on a veritable hunt for “slave laborers”. At the same time, resistance fighters attacked population registry and employment offices to prevent the registration of Dutch workers. In March 1943, the resistance attacked the Amsterdam population registry office. Students who did not sign a loyalty declaration to the German Reich were also mandated to perform forced labor in Germany. Of 15,000 students, only 2,000 signed, and around 3,500 were subsequently arrested and transported to the Reich.

The forced relocation of around 200,000 people from their villages for the construction of the “Atlantic Wall” also intensified strong anti-German feelings.

Following D-Day – the Allied landing in Normandy from 6 June 1944 on – the Netherlands was on the front line of war. Maastricht was liberated on 14 September, and on 17 September, Allied paratroopers (Americans, British, Australians, Poles) landed at Arnhem. The goal was to cross the rivers Maas, Waal, and Rhine. However, they failed to bypass the German defense lines at Arnhem, and the Allies had to withdraw with heavy losses.

On 20 May 1944, Curt Bloch published a poem titled The “Day D” (hit song) in his resistance magazine. He responded to the Battle of Arnhem with a text in his “Onderwater-Cabaret” on October 7, 1944.

In September 1944, the deportation of Jews was almost complete; over 100,000 had been murdered in concentration and extermination camps (see also Persecution of Jews).

Canadian and Polish troops captured the Walcheren Peninsula in October and November 1944. From there they liberated parts of the southern Netherlands in November and December 1944. The northeast of the Netherlands – including the town of Borne, where Curt Bloch was last hiding – was not liberated until April 1945 by Canadian troops.

The consequences to the civilian population in the last months of the war were significant. The Dutch exile government in London called for a strike by railway workers, to which the occupiers responded by restricting food supplies. Thousands of Dutch people starved to death in the winter of 1944/45, and both the administration and the economy collapsed.

Queen Wilhelmina returned to her country on 13 March 1945. On 5 May 1945, the Wehrmacht capitulated in Northwestern Europe, marking the end of the occupation of the Netherlands.

The title of a poem in the last OWC edition is Liberated! In it, Curt Bloch compares himself to a bird that was imprisoned for three years. Finally, he writes, his cage is now open. And for the liberators, he published his first and only poem in English: To The Allied Forces.

In total, an estimated 225,000 to 280,000 people out of nine million Dutch citizens died during the war and occupation, including around 2,000 people associated with the resistance, 20,500 through bombings or armed conflict, and 22,000 in the starvation winter of 1944/45. About 20 percent of the Dutch population was homeless at the end of the war. This affected survivors, like Curt Bloch, who hid from the Nazi regime during the war, evacuees who had lost their homes, and Dutch citizens who survived concentration camp and forced labor. They all tried to rebuild their lives in a devastated country.

The information on this page is based on publicly available sources and the book “Der lange Krieg der Niederlande” (The Long War of the Netherlands) by Peter Romijn which provides further details on the occupation period. It is available in Dutch and German. We thank the author very much for providing his information.