During the German occupation of the Netherlands, Curt Bloch lived in hiding, to avoid deportation to a labor or extermination camp. Under extremely challenging circumstances, Bloch developed a very personal form of resistance against the Nazi regime: “During the time I had to hide, I published a booklet of satirical poems in German and Dutch every week and circulated it among a small group.”

In reference to his fugitive situation, Bloch named his publication “Het Onderwater-Cabaret” (The Underwater Cabaret). The title alluded to a modern form of cabaret that had enthralled a large audience during the Weimar Republic (1918–1933). Cabaret performances typically consisted of a series of creatively crafted texts, songs, and scenes in which artists criticized societal injustices, mocked celebrities, and confronted the people with their perceived ignorance. Under Nazi rule, political cabarets were censored, closed, or forced to conform. The Dutch radio program “Cabaret op zondagmiddag” (Sunday Afternoon Cabaret) may have inspired Bloch to counter this fascist and anti-Semitic propaganda with his own subversive cabaret.

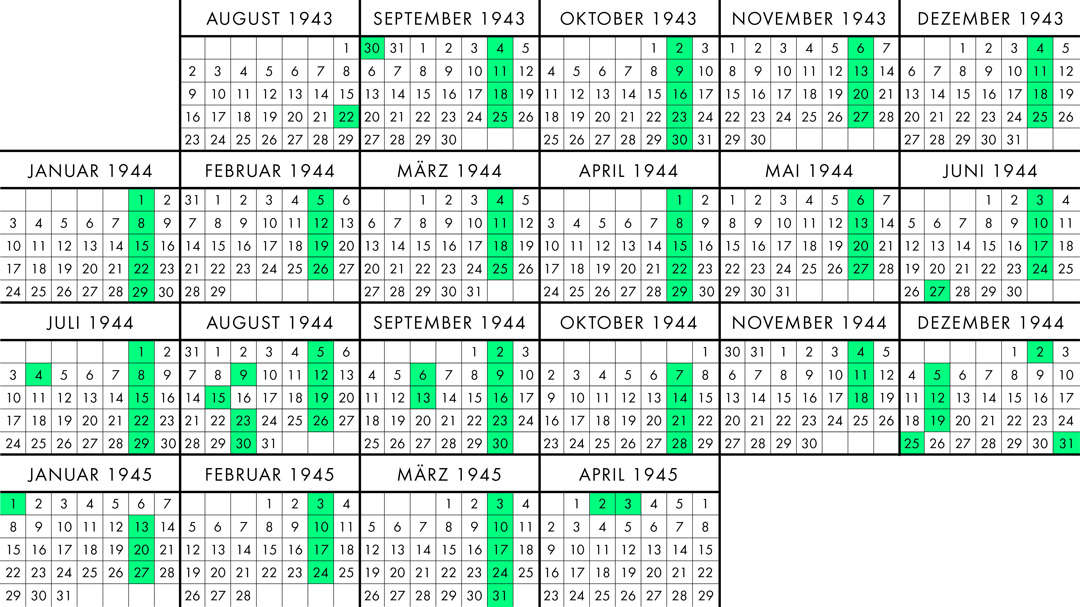

From 22 August, 1943, to 3 April, 1945, Curt Bloch conceived, wrote, designed, and produced 96 individual copies of “OWC” with a total of 492 poems spanning over 1,700 pages.

In 1943, he published 19 issues of his magazine. The following year: 61, including a special edition in July 1944 with no specific date assigned. The year 1945 included 15 magazines.

The magazines were typically published on Saturdays, but there were particularly productive periods, especially in August and September 1944, when he produced two issues per week.

Curt Bloch’s handmade booklets were slightly smaller than a standard postcard, measuring approximately 10 cm × 13.5 cm, and usually contained 16 or 20 pages.

All editions are fully preserved in numbered order. Only one poem, Farewell to ‘De Gouden Bommen’, had parts of the pages torn out, presumably intentionally, to remove any hints of a hiding place.

Curt Bloch mostly drew inspiration for his poems from journalistic newspaper articles, occasionally from illustrations, advertisements, or press photos. Starting from the 19th issue, he pasted his clippings into the booklets, hand-wrote dates on them, and sometimes added source references.

In the first year of the OWC, Curt Bloch published 111 poems; in the second year, 302 poems (plus nine in the special edition); and in the third year, 70 poems. Most verses were written in rhymed quatrains, some as couplets or tail-rhymes.

For each issue, he composed a series of self-contained contributions. The number of contributions varied: mostly four to six, but in issue 5 of 1943, there were twelve, and in issue 12 of the same year, only three. Since his readership included both German fugitives and members of the Dutch resistance network, he rhymed in both Dutch (277 poems) and German (214 poems) – except for one single English poem: To the Allied Forces. The fact that he used the language of the hated occupiers led Bloch to provide a justification in one issue of his magazine.

The Underwater Cabaret primarily dealt with current events of the time. Many contributions satirized well-known representatives of the Nazi regime, and some even dedicated entire poems to them. Besides Adolf Hitler and Joseph Goebbels, who appeared most frequently in the verses, other figures such as Heinrich Himmler (Reich Interior Minister), Joachim von Ribbentrop (Reich Foreign Minister), Gerd von Rundstedt (Commander-in-Chief West), as well as foreign dictators Benito Mussolini (Italy) and Francisco Franco (Spain) were also targets for ridicule. Prominent Dutch fascists like Arthur Seyß-Inquart (Reichskommissar of the Netherlands), Anton Mussert (founder and leader of the Nationaal-Socialistische Beweging, NSB), and Maarten van Nierop (NSB member and editor of the Nazi-controlled Twentsch Nieuwsblad) were also targets of his ridicule and mockery.

Another major theme of the OWC was the everyday experience of the occupation, including hunger, strikes, and raids. Bloch’s lyrical self also provided deep insights into his emotional world: concern for his family, especially his beloved sister Helene; despair and impatience in hiding; frustration over his isolated situation; gratitude for any form of support; joy at the victories of the Allies; and, repeatedly, hope for a swift return to freedom. Bloch’s rhymes display a wide range of emotions and changing moods depending on the course of the war.

Although Bloch often addressed his verses to unattainable literary recipients, his readers could still find themselves in them, especially since they usually ended with hope for an imminent end of the war and liberation by the Allies. For the post-war period, Bloch wrote the text To My German Readers, in which he earnestly asked them to wake up and learn from the mistakes of the past.

Bloch also let his readership in on the challenges of his secret publishing activities. When the Allies did not advance quickly enough in his view and he had to wait a long time for good news, he lamented the resulting lack of topics. Paper became scarce, and so did newspapers and magazines – his main sources of inspiration. In April 1944, he wanted to completely stop working on the Onderwater-Cabaret and wrote a frustrated Farewell to the OWC, but a week later, he resumed his work and distributed the next issue.

At one point, Bloch imagined having to wait a quarter of a century for liberation. This thought experiment resulted in the anniversary poem 25 Years of OWC – a retrospective from the year 1968 on a long period of life in hiding.

With his very last poem, the Overwater Finale of the OWC, Curt Bloch bid farewell as publisher, editor, author, designer, and producer all in one – forever.

While the first covers of the OWC magazine were in black and white, Curt Bloch designed the covers of his magazine in color from the 17th issue in 1943. He cut out letters, images, and shapes from various print media and glued them onto the cover paper.

In July 1944, Bloch decided to abbreviate the name of his magazine on the cover. Until issue 32 of the second year, he used the title “Het Onderwater-Cabaret.” From issue 33 onward, he used the abbreviation “OWC.” He retained this acronym on the cover until the final magazine.

If the lettering was not applied by hand, Curt Bloch placed cut-out letterforms for the title HET OWC at different positions on the cover.

Just as with the name of his magazine, Bloch’s cover design also refers to the characteristic popular culture of the Weimar Republic. His designs reference the artistic technique of collage, which was also used in contemporary mass media. Satirical and politically provocative collages by artist John Heartfield for the socialist Arbeiter-Illustrierte Zeitung were particularly well-known.

An important element of political cabaret was and is music. For this reason, Bloch turned many of his poems into songs. He referred to them as hits, songs, or ballads and structured the text as verses with choruses. In one case, with the Resistance Song, Curt Bloch even created a musical notation.

Cabaret artists, collage artists, and Curt Bloch – who, as a trained lawyer, did not have formal design training – share the fact that they created unique small artworks with the simplest materials and means, using creativity, improvisational talent, and subtle humor.

From issue 4 of the third year onwards, Bloch wrote his poems with ink on wood-containing paper, mostly in cursive, and consistently in block letters. In a final step, he sewed the sheet folds together. Each booklet is a unique work of craftsmanship and design. Here is an overview of the diversity of OWC covers.

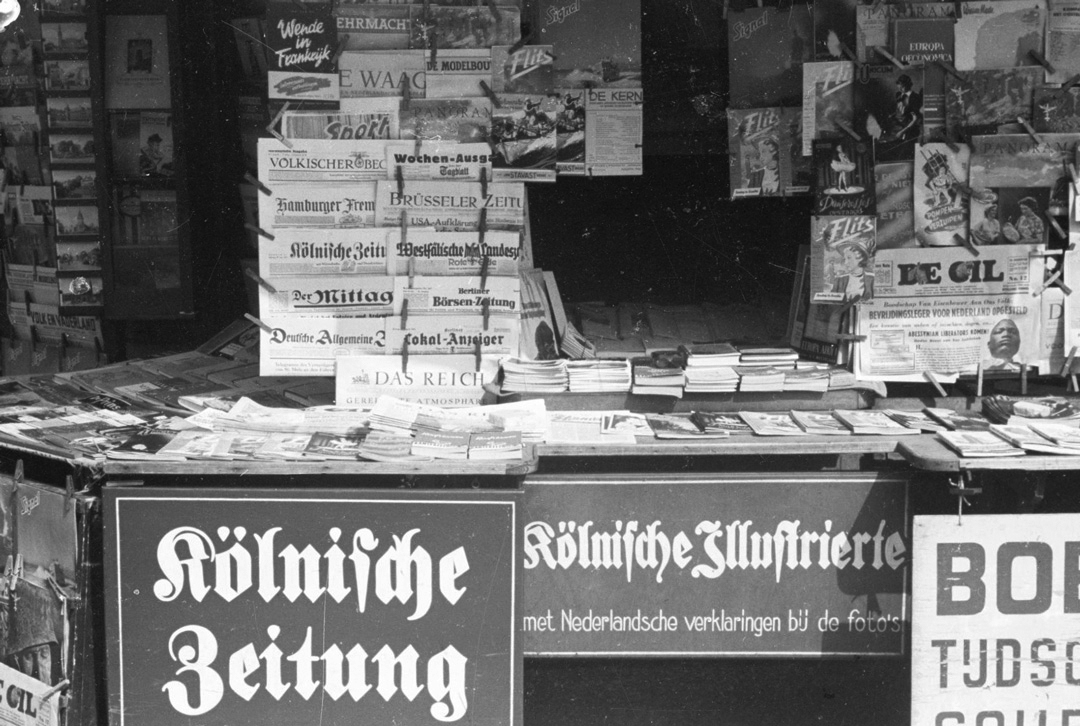

Like the famous cabarets of the Weimar Republic, Curt Bloch drew inspiration primarily from current societal or political events. His network provided him with Dutch and German print media, the content of which was often influenced by propaganda and censorship by the occupying power. In the Onderwater-Cabaret, he excerpted reports from the official NSB (Dutch Nazi) party organ Volk en Vaderland and newspapers such as Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant, Twentsch Nieuwsblad, Het Algemeen Handelsblad, De Courant, Katholieke Illustratie-Zondagsblad, Het Nationale Dagblad, as well as the independent resistance newspaper Trouw.

Bloch’s German-language readings included Das Reich, Koralle, Libelle, Illustrierter Beobachter, Das Illustrierte Blatt (later Neue Frankfurter Illustrierte), Deutsche Illustrierte, Münchener Illustrierte Presse, Hamburger Illustrierte Zeitung, Hamburger Fremdenblatt, Stuttgarter Illustrierte, and Kölnische Illustrierte Zeitung.

The weekly reading circle of the “Onderwater-Cabaret” began in Curt Bloch’s immediate environment, with the people who provided him with shelter, fellow fugitives like Karola Wolf and Bruno Löwenberg, and members of the resistance movement in Enschede. Once the window shutters were closed at night, Bloch could leave his hiding place. He often sat with his hosts and their visitors in the living room, where he could personally perform the cabaret pieces. However, his audience also included other fugitives and their supporters in different homes. Based on his resarch, Gerard Groeneveld, a Dutch historian and author (Het Onderwater Cabaret) estimates that the booklets reached up to thirty people. However, the exact number of readers and their names had to remain unknown due to the clandestine nature of the operation.

In addition to the diaries of Anne Frank, Victor Klemperer, and other chroniclers, whose records became invaluable testimonies, Curt Bloch’s “Onderwater-Cabaret” now offers us another, very personal glimpse into life during the Nazi era.

Despite the extensive secret handovers required for circulation, Curt Bloch’s resistance operation remained undiscovered. All 96 editions were returned to him in good condition. After the war, he emigrated to the USA, where he had the booklets bound into four collected volumes.

For decades, the original booklets remained largely unnoticed on the shelf because Bloch’s children and grandchildren had no direct connection to Europe, European 20th-century history was not extensively taught in their schools, and they only learned German as a foreign language as young adults. Despite having acquired language skills in the meantime, it was a challenge for them to understand Curt Bloch’s handwritten verses, which were filled with numerous abbreviations and outdated terms. Nevertheless, they always wanted to learn more about the “Onderwater-Cabaret” and make Curt Bloch’s creative legacy accessible to all interested parties. Finally, about 80 years after its first publication, this unique historical document can be presented to a worldwide audience.

There are numerous similarities in the biographies of Curt Bloch and Anne Frank. They were both born in Germany and moved to the Netherlands due to increasing anti-Jewish persecution – Bloch as a young lawyer and Frank as a four-year-old with her family. Both went into hiding in the summer of 1942 to protect themselves from deportation and murder. Their works – Bloch’s magazines and Frank’s diary – also exhibit parallels: both were created in hiding, an extreme situation marked by existential fear and social isolation. Anne Frank’s diary covers the period from 12 June, 1942, to 1 August, 1944, while Curt Bloch’s “Onderwater-Cabaret” was published slightly later, from 22 August, 1943, to 3 April, 1945. Both works contain observations of daily life and provide insights into the authors’ emotions. Both authors recorded in handwriting what moved them during this time – mostly in Dutch, not their native language.

However, there are also differences: When Anne Frank began her diary, she was preparing to celebrate her 13th birthday; Curt Bloch was already 33 years old when he released the first edition of his “OWC.” Anne Frank occasionally read passages from her diary to fellow hideaways; Bloch did the same but primarily distributed his booklets to other houses so that other fugitives and resistance members could read them. Anne Frank’s diary comprises about 290 pages, while Curt Bloch left behind more than 1,700 pages with his “OWC” alone (he also wrote smaller individual works). Anne Frank recorded approximately 25 poems in her diary, while Curt Bloch exclusively wrote poems in his “Onderwater-Cabaret” – nearly 500 of them. The Frank family hid in Amsterdam in the northwest of the Netherlands, while Bloch found refuge in the eastern region of Enschede. Anne Frank and her sister Margot died together in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. Only their father, Otto Frank, survived. Curt Bloch remained in hiding until liberation, when he was 36, and survived as the sole member of his family.

Anne Frank’s diary was published in 1947 and later translated into many languages. The public only became aware of Bloch’s magazines starting in November 2023, thanks to Gerard Groeneveld’s extensive Dutch publication, followed by international media coverage, exhibition activities at the Jewish Museum Berlin, and, not least, this website.

In addition to the diaries of Anne Frank, Victor Klemperer, and other chroniclers, whose records became invaluable testimonies, Curt Bloch’s “Onderwater-Cabaret” now offers us another, very personal glimpse into life during the Nazi era.