In the early 20th century, before World War II, the Jewish population was largely integrated into Dutch society. So after the Wehrmacht invaded, in May 1940, German authorities insisted that they would not impose anti-Jewish policies in the Netherlands. Soon that changed. Anti-Semitism was at the core of Nazi ideology, and the mass extermination of European Jews was one of Germany’s main goals. Within a few months, Jews in the Netherlands were systematically excluded from the society to which they had belonged for generations. Their legal protections and rights were eliminated and replaced with arbitrary restrictions.

The first Nazi actions foreshadowed a dark future. Militants of the Dutch Nazi Party (Nationaal-Socialistische Beweging, NSB) marched through the streets, attacked Jews, and vandalized Jewish businesses and synagogues. The hatred against Jews was translated into concrete policies, carried out step by step by the German occupiers and their Dutch collaborators from the autumn of 1940.

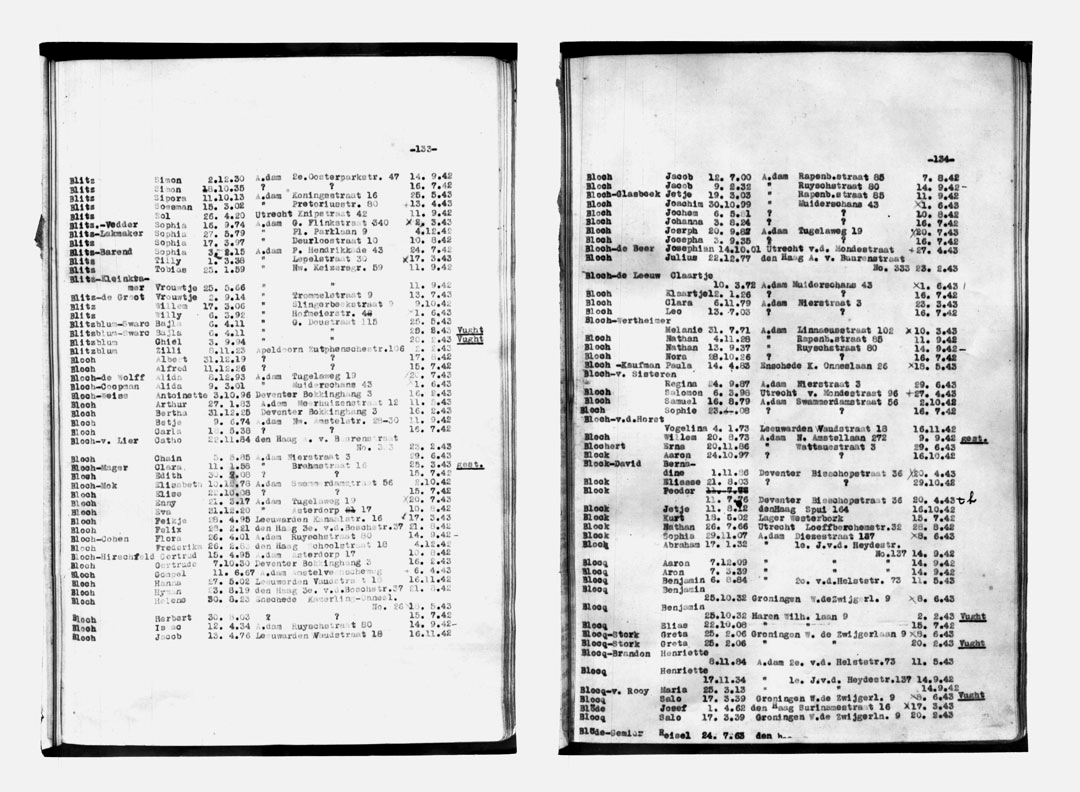

In September 1940, all Jews were required to register with the state.In October, they had to disclose and register their economic property and carry new official identity cards marked with a large black “J.”

On 4 November, another Nazi decree dismissed around 2,500 Jews from positions in the public service. Only a few Dutch citizens expressed sympathy for the affected individuals, and public protests were limited to schools and universities.

Most Dutch Jews complied with the registration requirement, either out of fear of reprisals or because they saw no alternative. In February 1941, prominent Jews were ordered to establish a Jewish council (Judenrat) to ensure that Jews followed Nazi directives, as was the case in other countries occupied by Germany.

In a speech at the Amsterdam Concertgebouw on 12 March 1941, Arthur Seyß-Inquart announced that Jews would be completely excluded from Dutch social and economic life. He said: “We will beat the Jews wherever we meet them, and those who go with them will bear the consequences.”

In September, the Chief of the German Police in the Netherlands, Hanns Rauter, declared that Dutch authorities were no longer responsible for the Jews. While there were some protests by Dutch officials against the segregation of the Jewish population, they did not lead to tangible consequences. The Dutch government in exile also did nothing to counter the anti-Jewish policies.

Arthur Seyß-Inquart and Hanns Rauter appear in Curt Bloch’s poems repeatedly since they are main figures responsible for his life-threatening situation. Bloch wrote the cynical Seyss-Inquart has birthday on the occasion of Seyß-Inquart’s 52nd birthday, 22 July 1944, and predicted that the Reichskommissar would enjoy no more birthdays. For Rauter, the Nazi police commander, Bloch wrote an obituary (In memoriam Rauter †) and celebrated a rumour that Rauter was assassinated in March 1945. Rauter was seriously wounded in the attack, but he survived.

During 1941, Dutch Jews lost their legal status as citizens. They were subjected to a new set of binding regulations that applied only to them. After a raid in June 1941 in Amsterdam, during which more than 300 Jewish men were deported and murdered in Mauthausen, the entire country experienced a wave of anti-Jewish violence. Dutch National Socialists attacked synagogues and other buildings in Jewish communities. In the autumn of 1941, large-scale raids also took place in Gelderland and the Twente region, where Curt Bloch had been living since 1940.

The German authorities imposed numerous prohibitions that severely restricted the Jewish population’s freedom of movement. Public buildings and facilities such as markets, parks, restaurants, theaters, cinemas, swimming pools, concert halls, sports facilities, public libraries, and museums could no longer be visited or used by Jews. Jewish students were excluded from schools and universities after the summer holidays.

Jews were prohibited from practicing professions, which outlawed the work of many doctors and lawyers. Jewish businesses and companies were confiscated based on an ordinance issued in March 1941. The persecution of Jews led to a dehumanization of interpersonal relationships and a profound alienation between the persecuted and Dutch citizens. Dutch society and its institutions did not offer adequate protection to the threatened minority.

In August 1941, all Jewish property was confiscated. Jews had to transfer their entire bank balances to a specific bank, which effectively placed the entire wealth of Dutch Jews in the hands of the German authorities. All Jewish-owned properties and possessions were seized.

“Why don’t Jews have the same rights as others? Why have they been taken from their homes? Why should we hate them?” While hiding, a young boy asked his mother these and other questions in Curt Bloch’s poem “A Little Person in Hiding Asks,” published in the OWC magazine on 25 September 1943.

From 3 May 1942, all Jews were required to wear a yellow star on their clothing in public. Fearing reprisals, the Jewish Council complied with the order. The introduction of the yellow star not only marked the culmination of segregation but also marked the beginning of deportation. In a secret document, Arthur Seyß-Inquart wrote to his top officials that the star requirement applied to all Jews “eligible for resettlement,” his euphemism for deportation to German-occupied Poland, where the Nazis ruled with ruthless terror and had already established several ghettos, concentration and extermination camps.

On 20 June 1942, Adolf Eichmann ordered the first Jewish deportations from the Netherlands. The operation was coordinated by the German police, with collaboration from the Dutch authorities and police apparatus.

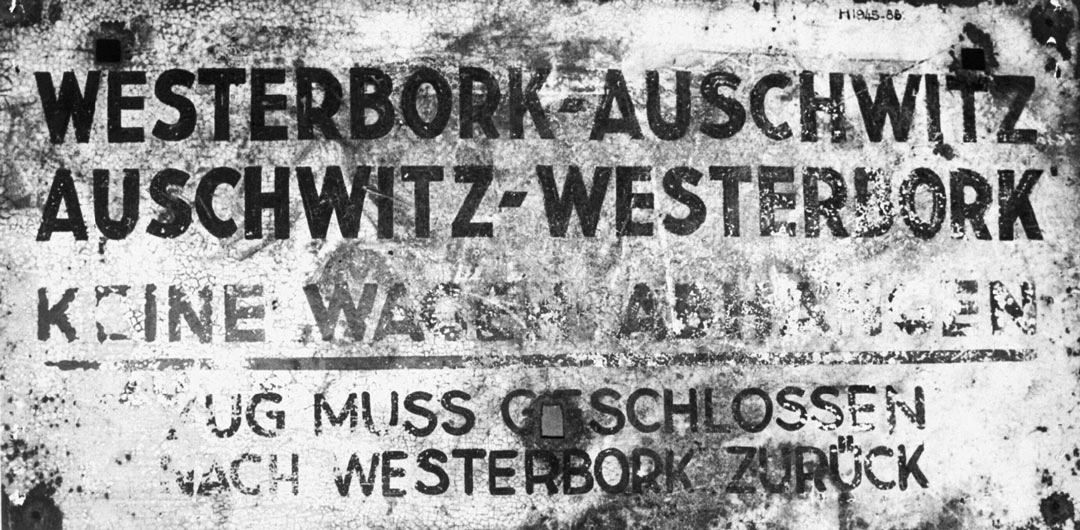

The systematic deportation of Dutch Jews began on the night of 14–15 July 1942, when the first train carrying 962 people departed from Amsterdam Central Station to Westerbork. On the same day, the first 1,135 people, mostly German Jews, were deported from Westerbork to Auschwitz.

The journey to Bergen-Belsen in northern Germany could be completed in one day, while the trips to Auschwitz in Silesia and Theresienstadt in Bohemia took two days, and the trains took three days to reach Sobibór in eastern Poland. When they arrived at their destinations, deportees were completely exhausted and desperate for fresh air. Sick and elderly people often died during transport. Unlike Auschwitz, there was no selection in Sobibór; the sole purpose of the camp was immediate killing.

Curt Bloch’s mother, Paula, and his sister, Helene, were arrested in May 1943. In the same month, they were deported to Poland via the Westerbork transit camp and murdered in Sobibór.

“Only one thing was true: The Jews are annihilated.” This is a line from the poem Women’s Autarky in the OWC magazine from 19 February 1944. Curt Bloch knew exactly how endangered he was as a Jew, which is why he remained in hiding until the liberation of Enschede.

In total, over 100,000 Jews from the occupied Netherlands were deported to concentration and extermination camps. Of these only just over 5,000 survived.

In hardly any other country was the anti-Semitic persecution and extermination policy as “efficient” as in the Netherlands: out of the approximately 140,000 Jews who lived there in 1940, 107,000 fell victim to this Nazi policy. A deeply rooted, well-integrated group in the Netherlands was systematically excluded from society in a very short time, and four-fifths of them were killed.

Some citizens and various resistance groups acted selflessly and heroically to protect their Jewish compatriots from deportation. However, most Dutch citizens did not recognize or acknowledge the enormous vulnerability of the Jews, or perhaps did not want to see it, possibly because they were preoccupied with their own problems.

According to a study by the Anti-Defamation League, over 800,000 people in the Netherlands and over 8 million people in Germany hold anti-Semitic attitudes. Many respondents have reported never having heard of the Holocaust (Netherlands: 13%, Germany: 5%).

The German Federal Agency for Civic Education has noted that violence against Jews in Europe has been increasing for years.

According to a July 2023 study by the Konrad-Adenauer Foundation, a large majority of the German population rejects anti-Semitic statements. However, agreement with anti-Semitic statements is increasing among individuals with less formal education, people with Muslim and/or immigrant backgrounds, and within the AfD (Alternative for Germany) party’s supporters.

We thank the scholar Peter Romijn, former research director of the NIOD and Professor Emeritus of 20th-century history at the Amsterdam University for sharing his research results about the persecution of Jews in the Netherlands. He is author of the book Der lange Krieg der Niederlande (The Long War of the Netherlands), which provides many details about the German occupation from 1940 to 1945.