During the German occupation, between 300,000 and 330,000 people went into hiding in the Netherlands. Many of them Dutch citizens trying to avoid forced labor for the German occupiers. Among the “Onderduikers” (people in hiding) were approximately 28,000 Jews, a significant portion of the 140,000-strong Jewish community in the Netherlands. Curt Bloch was one of them.

In July 1942, the third phase of Jewish persecution began in the Netherlands, transitioning from identification and isolation to deportation by the occupying forces. The call for registration led to heated debates in many Jewish families about whether to go into hiding or not. For many, going underground was completely out of the question, partly because the “Judenrat” was against it, arguing that not everyone had the opportunity to hide.

Additionally, it was unthinkable for many to be separated from their loved ones. Another obstacle was the extreme dependence on mostly strangers, and there were also practical concerns: for example, it would have been impossible to continue following all religious rules living with a Christian host family. And initially, many did not know – at least in the early stages of deportation – that a large part of those deported were killed upon arrival at a “labor camp”.

Curt Bloch’s mother Paula and his younger sister Helene, who had also moved from Dortmund to the Netherlands in 1939 due to reprisals against Jews, were arrested in May 1943 and interned at Westerbork camp. In the same month, they were transported in freight trains to the southeast of Poland. On May 21, 1943, both were murdered in the Sobibor extermination camp – Paula Bloch at the age of 60, Helene at the age of 19. Curt Bloch learned that his mother and younger sister “Leni” had been taken away – but he did not know what happened to them. On August 30, 1943, he sent Helene a moving greeting in his magazine, and dedicated the poem For mother to his mother on her birthday, April 14.

Going into hiding was an unknown phenomenon; none of those affected had any experience with it. But soon, the network of reliable helpers worked smoothly, and they managed to care for “their” people in hiding.

Most Jews had neither a place to hide with their entire family nor the opportunity to prepare properly for this step. Many of them found refuge in the countryside; there was more food during the occupation, and farmers could usually make good use of cheap labor.

Over the course of 1942, the provision of hiding places became better organized. Small hiding networks formed in various places across the country. Often at the center of these networks was a charismatic individual with many contacts in the area and a heart in the right place.

Financial resources were also necessary to shelter those in hiding. The amount demanded varied greatly. A few guilders per day was quite normal, but there are also cases known where 1,000 guilders per month had to be paid for a small attic room on a farm – today, the equivalent would be about 6,445 $.

This demonstrates that some shelter providers exploited the situation for profit. Especially Jews had to pay high “boarding fees,” as it was generally assumed that there were particularly high penalties for harboring them. And the higher the risk, the more expensive the shelter – at least that was the thinking. Regardless of the cost, it was generally more difficult for Jews to go into hiding: To find a suitable hiding place, they depended on non-Jewish relatives, friends, acquaintances, or business partners.

To commemorate living two years in hiding, Curt Bloch published the poem Even if I say so myself … in the OWC magazine on August 15, 1944.

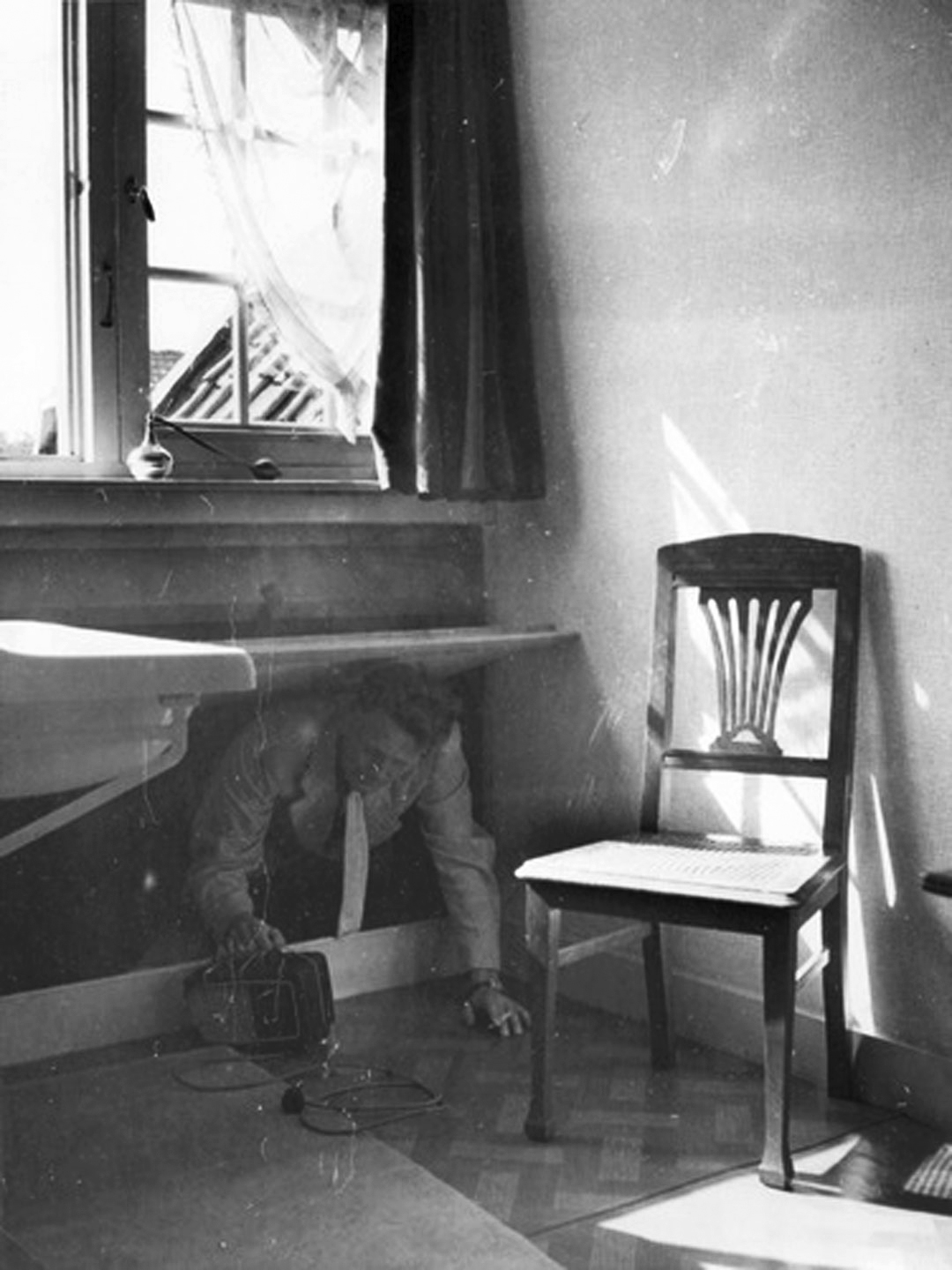

The hiding places varied greatly. In the city, space was often cramped, and the persecuted had to remain silent: the walls were thin, and any slight noise could have betrayed their presence to neighbors. In the countryside, there was more space, but that did not automatically mean better living conditions. Some of the hidden went into the forests, built huts, and dug underground tunnels. Later, rescuers regularly used vacant chicken coops to hide Jews – uncomfortable and of course freezing cold in winter. If danger threatened, those in hiding often had to flee in a hurry to find a new hiding place. It was more the exception to be able to stay for a long time in a single hideout (like Anne Frank’s family or Curt Bloch).

After the war, it was learned that some people had hidden in more than twenty different places in succession. Jewish children had to change their refuge on average 4.5 times.

When the persecuted moved to a new address, it was usually done in the dark. Being seen on the street was dangerous for Jews. Nevertheless, there were also Jews in hiding who went outside during the day. This mainly happened in the last two years of the occupation, when fake IDs were produced on a large scale, hardly distinguishable from real ones.

With each change of hiding place, along with fear, there was also the uncertainty of whether the new refuge would actually be safer than the previous one. Often, places near German troop quarters or police stations – right under the enemy’s nose – proved to be particularly suitable; the occupiers did not even consider that someone would dare to hide so close by.

Some of the persecuted found a relatively safe and affordable hideout with good facilities and enough space and privacy. The annex was one such place. But even there, people could not escape the physical and psychological deprivations of hiding.

Due to the extreme dependency as well as cultural, religious, and social differences, relationships between those in hiding and their helpers were sometimes quite complicated. In some cases, this dependency even led to excesses such as exploitation and sexual abuse. Especially girls who had to go into hiding without their parents were vulnerable and completely helpless in such a situation. However, there are also many examples where those persecuted and in hiding developed a special relationship with their hosts. Both sides often later saw these years as the most formative time of their lives. Like many survivors, Curt Bloch remained in contact with his Dutch helpers after his emigration to New York.

Not having to live in hiding and being able to move freely – this ardent wish was often expressed by Curt Bloch in his verses, e.g. in the poem Once peace will come in his magazine of 16 September 1944.

Of the 28,000 Jews in hiding in the Netherlands, many thousands were arrested – historians estimate that about a third of the Jewish “Onderduikers” were discovered, betrayed, and deported. (These are well-founded estimates; exact figures do not exist, inevitably due to the secrecy necessary for an illegal life at that time.) The arrest of Jews in hiding was mainly the result of a sophisticated reward system; with this, the Germans intended to entice police officers and civilians to betray those in hiding. The professional “Jew hunters” of the so-called Kolonne Henneicke received a bounty of 7.50 guilders for the capture of a Jewish “Onderduiker” – corresponding to a current purchasing power of about 56.40 $.

We would like to thank the historian Jaap Cohen and the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam of the generous provision of their information.